Annika Schlicht: Mein Seelenort … Das Museum - Deutsche Oper Berlin

Annika Schlicht: A place of serenity for my soul … The museum

Mezzo-soprano Annika Schlicht sings Fricka in Wagner’s THE RHINEGOLD. To get into her roles, she looks to classical art for inspiration – and finds characters that exude timeless truths

Museums are the places where I find respite from the madding crowd. Whatever country I find myself in, I always head for art galleries, collections, contemporary exhibitions. I’m starved of all that at the moment, what with the restrictions of the last year. The minute things began to open up again I booked slots and visited four museums in a week. Museums are places of peace where I can properly zone out. But they’re sources of inspiration, too, and I use them when I’m researching my roles and getting into character.

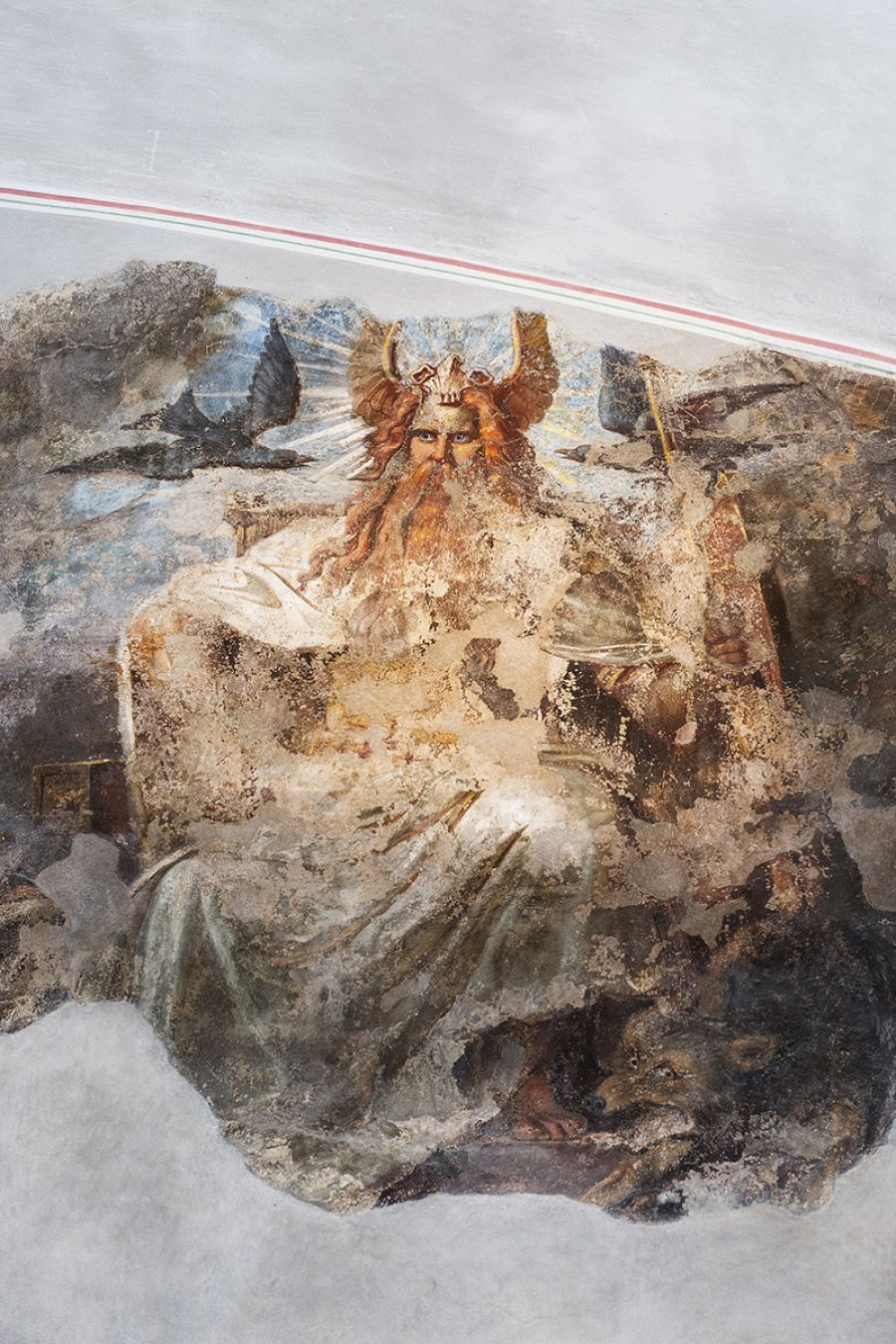

In 2019 I was Fenena in Verdi’s NABUCCO and spent a lot of time in the Pergamon Museum. Many times I looked up at the Ishtar Gate and got a real vicarious sense of how it must have been for Fenena to walk Babylon’s Processional Way five hundred years before the birth of Christ. At the moment I’m doing stints in the Vaterländischer Hall in the Neues Museum in Berlin. I’ve known the place since I arrived in Berlin in 2009 to study at the Hanns Eisler School of Music. And it’s taken on a new significance for me since I started working on Wagner’s RING OF THE NIBELUNG. The frieze in the Vaterländischer Hall depicts characters and tales from the Nordic »Edda«, a 13th-century collection of Icelandic myths. Wagner drew on the »Edda« for his RING, and I’m singing Fricka, Wotan’s wife, the goddess of marriage, home and household. I stand there surrounded by splendour, looking at the 19th-century murals: that’s Odin, Nordic lord of the gods, known as Wotan in the RING; the death of his son, Baldur; a drinking spree in Valhalla.

The frieze shows two Germanic warriors in a burial mound. The adornments that are part of their garb in the artwork are inspired by historical artefacts that were on display when the hall opened. For me, the only element missing from the Vaterländischer frieze – and it’s a big ‘only’ – is Fricka. And another thing was missing (for the audience): because of the pandemic the RING cycle couldn’t start off with THE RHINEGOLD, the preliminary ‘Vorabend’, which is meant to be the first element in the tetralogy and presents, among other things, the softer, anxious side of Fricka’s character. In September the cycle kicked off with THE VALKYRIE, in which Fricka has the whip hand, fed up with being constantly deceived and belittled by Wotan. She confronts him and gets him to do what she wants. Her principles are on display: as the goddess of marriage, she’s not going to tolerate his behaviour – but neither can she give him his marching orders. I kind of got parachuted into this big bust-up on stage. It wasn’t easy getting to that emotional place onstage without the back story as a run-up, because singing is a full-body experience. I had a real physical sensation of how much I missed singing THE RHINEGOLD in my debut performance.

There are human traits to Fricka’s character, yet she remains a goddess. But we do have one thing in common: I, too, have principles, even if I’m not quite as drastic as Fricka. Things like honesty, loyalty and helping other people are important to me. And principles are good for me in my work: I don’t drink alcohol the day before a performance, for instance, or when the rehearsals are coming to a head. I understand Fricka, including her stormy relationship with Wotan. I admire the way she jousts with him verbally. I like singing in German and the way it can come up with words like ‘far-sick’ (as opposed to ‘homesick’) and stand-alone terms like ‘feeling lonely in a wood’. German is a language I can paint with. Wagner’s works are speckled with Old and Middle High German words like ‘Klinze’ (a narrow gap), ‘kiesen’ (choose) and ‘Mähre’ (old horse) and he even makes up his own derivations like ‘böslich’ and ‘neidlich’. With the Rhinemaidens you get a great idea of his love of alliteration: »Weia! Waga! Woge, du Welle, walle zur Wiege! Wagalaweia! Wallala weialaweia!« That splurge of rhyme gets a lot of spoof treatment, but there’s nothing non-sensical about it: »Wag« refers to a stretch of agitated water and »waian« is a Germanic verb meaning »blow«.

Any study of Wagner and his body of work is always going to involve German history and sombre aspects of the composer’s biography, such as his anti-Semitism. I’m not particularly proud of being German. I don’t really do pride anyway. My sensibilities tend to be local or global. I’m from Stuttgart, so Stuttgart and my family there are home to me, deep down. But I’m happy being a European and citizen of the world. What is ‘German’ anyway? National identity is an artificial construct: culture, language, people are always in flux. And it’s not least museums that present the documentation of that. Ok, I’d still be able to sing my roles without having this intense contact with history and paintings and artefacts – but strolling through museums definitely help me to shrug into my roles, bodily, three-dimensionally.