Blick zurück – „Aida“ - Deutsche Oper Berlin

A retrospective – "Aida"

The audience that took its seats in the Deutsche Oper Berlin on 29th September 1961 to see Wieland Wagner’s epochal production of AIDA – the third premiere to be presented at the newly inaugurated opera house, which had opened its doors five days before – was greeted by a stage devoid of pharaonic kitsch and gently waving palms. True to his creed of a “clearing out of the stage”, Richard Wagner’s grandson was always going to reject a clichéd Egyptian backdrop in favour of emphatically exotic and unfamiliar scenery and costumes representing the “absolute” conflict between love and death which he saw as being at the core of the opera. Here in Act 2, as in other long stretches elsewhere in the production, his dark sets, which incorporate masks, fetishes and a gigantic phallus in Amneris’s chambers, created an archaic and conspicuously fictional “Africa”.

The approach adopted by Wieland Wagner to AIDA may well have been the first to shake up the entrenched visuals and address the work as a “living piece of theatre”. To this end, Wagner harnessed modern stylistic devices, in his mind the only conceivable strategy. This, after all, was what he had been doing with his “Neo-Bayreuth” aesthetic since 1951, when he deployed it for the first time in his PARSIFAL at Richard Wagner’s home venue, the premiere that opened the first post-war Bayreuth Festival.

This AIDA was a psychological treatment by a director for whom “the entire music of the 19th century was rooted in psychology”. He distilled the action to archetypally “human situations and predicaments” – and used malleable symbols to ensure that this dramatic, psychological core held abstract sway over the visual aspect.

A key factor in this production is its inversion of the conventional use of darkness and light. Wagner, for whom the triumphal march was a “tragic scene” depicting the clash between love and a disruptive principle of order, presents the procession and the temple scene as nocturnal events but illuminates the crypt (his location for the two protagonists’ transcendental ‘death-in-love’ scene) in the “diffuse light of a supernatural day, a day that forms part of a different, superior world”.

Among the offerings on the opening programme, the AIDA premiere was the work that went down best. Berlin critics and audiences considered it one of the triumphs of the 11th Festival, and the performance was also broadcast live over the radio. A Wieland Wagner premiere was always going to be a sensation. Although not a label in common use at the time, Wagner’s “notoriety” often produced booing at the end of his premieres. Artistic Director Rudolf Sellner was pushing for renewal, debate and contemporary theatre and was only too glad to enlist Wieland Wagner to help draw crowds to his new venue – the material being not (Richard) Wagner but Verdi.

Some notices criticised the uniformity of Wagner’s approach and his attitude towards Verdi’s lyrics, which Wagner tended to try to smother.

Johannes Jacobi, for Die Zeit, wrote:

The scion of Bayreuth has staged "Aida" as Verdi’s "Tristan und Isolde". The director has come up with an "African mystery" to add to his Neo-Bayreuth mysteries stage. Many spectators would have thought it natural that Wieland Wagner would attempt to trump Locle’s and Ghislanzoni’s set depicting a pharaonic high culture, even though Verdi, the composer, took a keen interest in the details of the libretto to the extent of writing the death scene of Radamès and Aida himself. But here we see Wieland Wagner as director setting himself above Verdi the musician, as he so often does relative to Richard Wagner. He bathes in a green and violet twilight what Verdi’s music renders as boiling sunlight. […]

One aspect sticks out from a production that, in parts, was surprisingly striking in its visuals: Wieland Wagner’s staging of what might be termed Verdi’s "Tristan" dwelt only on the psychology of the protagonists, on Radamès, Aida and Amneris, yet the director enveloped these three highly sensitive characters in a prehistoric primitivism (splurging on masks and costumes in the process). He has given us an Africa dominated by totemism and fetishism. Were Richard Wagner’s "Ring of the Nibelung" to be rendered from German into Greek and performed at Bayreuth, such an arbitrarily archaic version would still be able to count on a degree of symbol recognition on the part of the spectators. For audiences to grasp Wieland Wagner’s "Aida" semiotics, however, they would have to be simultaneously leafing through the ethnological tomes of Frobenius and Thurneisen. (https://www.zeit.de/1961/41/die-welt-zu-gast-in-berlin/komplettansicht)

Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt writes in the FAZ:

Nothing remains of Verdi’s and Ghislanzoni’s settings, not the palace, not the gate, not the riverside palms. Instead, we have a huge procession of exotic war dances in the fourth scene, a succession of brief performances by assorted groups: priests wearing man-high masks, crude and gaudy; headhunters toting their trophies; archers; enormous totem poles. The stage is riot of unfettered exotica, meta-African, a motley bundle of references to the roots of Aztec, Etruscan, central African and Middle Eastern mythology. […] Wieland Wagner’s repudiation of museal motifs is breathtaking in its radicalism but puts him a hair’s breadth from precisely those optical Hollywood excesses that he is set on distancing himself from.

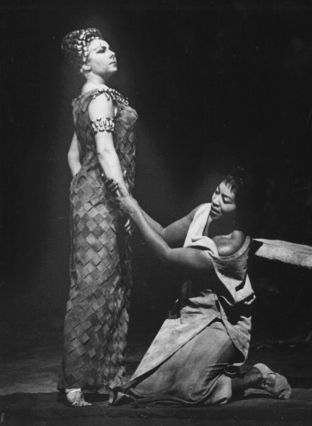

The focus of the action has also shifted. Amneris is now the star of the piece, and this is alone down to the brilliance of Christa Ludwig’s singing and acting. Aida’s body language and posture, minimalistic in her gestures and mostly lying down or cowering, foist on her a passivity that makes her love seem impulsive and second-grade in comparison to the jealousy of Amneris. It is consistent with the director’s urge to clear out the stage that the standard dance routines have vanished along with the principal emotions and the ballets have been substituted by a collective twitching and jerking of bodies. Only in Amneris’s chambers do we get a mass belly dancing scene reminiscent of Gertrud Wagner’s Tannhäuser bacchanal.

(H.H. Stuckenschmidt, Zwischen Bel canto und Regiewillkür, FAZ, 4.10.1961, p. 24)

Praise was lavished on conductor Karl Böhm and the singers – first and foremost Gloria Davy as Aida, Christa Ludwig as Amneris, Jess Thomas as Radamès and Walter Berry as Amonasro – albeit with sceptical whisperings as to whether the Wagnerian production would survive into future runs without such a top-notch cast to carry it.

From our present-day perspective, the means chosen by Wagner to – as he put it in an interview with dramaturg Horst Goerges – counter “Egyptian art norms and wrong-headed opera monumentality” may appear bizarre. The things that Wagner claims are taken “not from an Egyptian museum” but rather “from a holistic idea of Egyptian-ness” actually resemble a random selection of artefacts from a museum of “ethnology” (as Jacobi, too, observes).

To put it bluntly: the “colourful fragrance” of the “African enigma” (Wagner) is tainted by the fug of an “imperialist spectacle” (Edward Said) – a spectacle in which the presentation and perpetration of colonial rule are inextricably linked. Wagner provokes his bourgeois audience with art-imbued symbols on a monumental scale, symbols that the audience nonetheless reads consistently as ‘African’. A notice in the Frankfurter Rundschau describes a “nightmare from Africa”; the Süddeutsche Zeitung calls the production “Wieland’s L’AFRICAINE”. Also, the black soprano Gloria Davy, who, in 1958 at the Met, had become the first African-American to assume the role of Aida, is doubtless taken by the audience to be an authentic visual representation of the “pre-dynastic” (Wagner) and dark ‘Africa’ imagined by Wagner.

In Act 2, for instance, when the director has the Ethiopian prisoners bear totems, masks and ritual objects as visual symbols of their colonialist and racist subjection, he is reproducing this very subjection himself through his poorly thought-through cultural appropriation.

All this is allowed in art, of course, but it does not get around the question as to the extent to which Wagner’s production can be said to have a boundless and timeless relevance. Regarding the time aspect, we should not forget that much of the 1961 audience might have been sitting in the same auditorium 20 years previously – and the racism of the National Socialist era was not simply erased with the end of the Second World War. Moreover, Wieland Wagner, in his capacities both as director and as artistic director of the Bayreuth Festival, represents a thread of continuity in the post-war period. In his book published this year, Hier gilt's der Kunst: Wieland Wagner 1941-1945, Anno Mungen explores the years Wagner spent in the lee of National Socialism.