König der Oper - Deutsche Oper Berlin

What moves me

King of opera

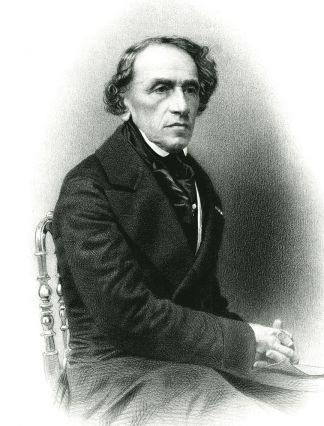

Giacomo Meyerbeer’s operas chimed with the mood of a society reaching out for new ideologies. An essay by Jörg Königsdorf

Dinorah ou Le Pardon de Ploërmel (konzertant)

Opera by Giacomo Meyerbeer

Conductor: Enrique Mazzola

With Rocio Perez, Florian Sempey, Philippe Talbot et al.

4, 7 March 2020

Les Huguenots

Grand Opéra by Giacomo Meyerbeer

Conductor: Alexander Vedernikov

Director: David Alden

With Liv Redpath, Olesya Golovneva, Irene Roberts, Anton Rositskiy, Andrew Harris / Ante Jerkunica et al.

2, 9 February; 1, 8 March 2020

Le Prophète

Grand Opéra by Giacomo Meyerbeer

Conductor: Enrique Mazzola

Director: Olivier Py

With Gregory Kunde, Clémentine Margaine, Elena Tsallagova, Derek Welton, Gideon Poppe, Thomas Lehman, Seth Carico et al.

23, 29 February; 6 March 2020

We can assume that April 16th 1849 was one of the happiest days in the life of Giacomo Meyerbeer. It was the night of the premiere of his LE PROPHETE and Meyerbeer had at last silenced all those who, during their long, drawn-out wait for the composer of LES HUGUENOTS to come up with another grand opéra, had been murmuring with anti-Semitic asides that his creativity had peaked. He had also silenced those who had worried that his duties as Royal Prussian Director of Music, his hectic travel schedule and his work on the new productions of his LES HUGUENOTS and ROBERT LE DIABLE had so drained him that he had had no time left over to write a new opera.

All those reservations were now dispelled. His triumph, which his critical colleague Hector Berlioz described as »towering and without parallel«, had exceeded the expectations of Parisian society. Verdi, 22 years his junior, had yet to pen his masterpieces and Richard Wagner, if he was in the news at all, was known more as a revolutionary on the run. Meyerbeer was the man of the moment, the undisputed king of opera. On that evening the Assemblée Nationale had been inquorate, such was the urge among deputies not to miss the premiere. Expectations were high not least because Meyerbeer’s LES HUGUENOTS in 1836 had been truly innovative, establishing the grand opéra style that had since been espoused across Europe. With that work depicting the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre he had shown that historical events could serve as a subject in their own right and not simply as a backdrop for the grandiloquent emoting of great singers. The exciting thing about LES HUGUENOTS was the way it had meticulously charted, in action and music, the unfolding of a real-life disaster that erupted at the end of the opera, burying the characters beneath it like a tsunami.

In the aftermath of that international triumph audiences were hungry for more tales of riveting drama and destiny to compare with that of the LES HUGUENOTS lovers, Raoul and Valentine. But Meyerbeer let them stew, writing his next opera in his own good time. He and his librettist Eugène Scribe once again drew on material dating back to the time of the Reformation, albeit viewed from a quite different perspective. Whilst the understated main role in LES HUGUENOTS is played by the amorphous populace, which becomes more radical and more anonymous as the story progresses, in LE PROPHETE we are presented with an upstanding innkeeper, who finds himself leading a radical sect as a result of his justified anger at an injustice his family has suffered. In the end Jean realises that the powerbrokers within the sect are just as corrupt as the existing authorities. By the time of the premiere the historical material had become acutely topical: few operas before or since have drawn as close a parallel with political events as LE PROPHETE, which was seen as a commentary on the revolution of 1848, which had only recently been quelled. Meyerbeer had witnessed the upheaval at first hand in Paris and had adjusted parts of his already-completed opera accordingly.

As in LES HUGUENOTS, so in LE PROPHETE it is religion that is used as a way of generating hatred instead of reconciliation. This misuse of faith is revisited by Meyerbeer in his final grand opéra, VASCO DA GAMA / L’AFRICAINE, and amounts to a leitmotif running through his body of work – and through his life. Despite his professional success, as a Jew he was fully aware of his outsider status. And where the malleability of the masses and their capacity for learning the lessons of history are concerned, Meyerbeer’s operas have had depressingly little influence – and are probably more relevant today than they have ever been.