Heldendämmerung - Deutsche Oper Berlin

Aus dem Programmheft

Twilight of heroes

Reflections on the 2010 production of Rienzi at the Deutsche Oper Berlin ... an essay by Katharina John

Richard Wagner

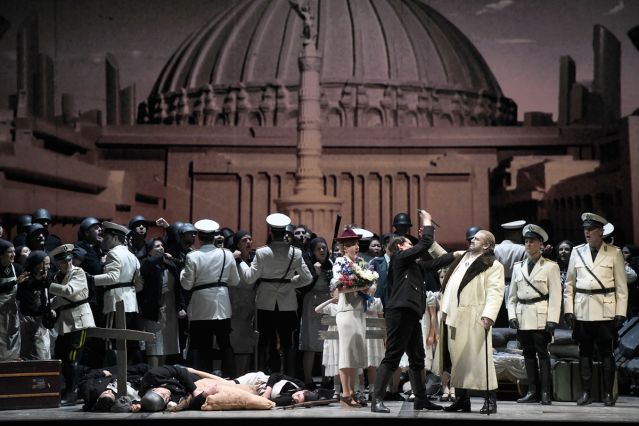

RIENZI, THE LAST OF THE TRIBUNES

We would like to thank the Unitel label for kindly granting us permission to broadcast the film. A DVD of this production is available in stores, for example in the

Amazon-Shop

Passengers perusing the »Berliner Fenster« overhead bulletins on the underground may be aware of a new advertising campaign entitled »Heroes of Berlin«, the initiative of an advertising agency »specialising in socio-political affairs« on behalf of a local newspaper. Any Berliner wishing to be seen as a »hero« can visit a certain website and be assigned an appropriate »deed« to perform. According to the agency, the aim is to spur as many Berliners as possible to »get involved in tackling problem zones across the city on a voluntary basis«. The choice of the term »problem zones« to denote the rising number of social inequalities and injustices suggests that the advertisers see these issues first and foremost as cosmetic problems. Yet it is precisely the advertising and entertainment industry that, in this »post-heroic age«, when soldiers no longer fall in battle or die a heroic death in the field of conflict but »die in the war on terror«, bandies around terms such as »hero« and »heroism«. The media use the labels as a way of raising certain individuals from the run-of-the-mill and making them stand out from the crowd. Political systems instrumentalise the »hero« badge to edify people and foster virtuous conduct in the public interest. The title of »Hero of Labour« was conferred on workers in the GDR who considerably exceeded their production quotas; in West Germany blood had to be shed before a worker was deemed a hero – his own, it should be said, and only in limited quantities: »Be a hero and donate blood« was the slogan used by the German Red Cross, an appeal that has been replaced by the more sanitised, less heroic »Heroes like you and me« - far removed from the original idea of heroism. »Hero« today is a PR label that serves as a description of the true or assumed potential of a human being who is in a position to be selfless, helpful or – in the mirror of the media – just fascinating.

Heroism

Along the way we lost sight of the enormity of the original meaning of the word, which stems from a mix of specific characteristics and is reliant on a social matrix that defines heroism and puts a value on the relevant deed. Heroes are the epitome of virtues that are arguably universal. Heroism is synonymous with »action« and »decision-making«. All attempts to classify »people enduring pain« as heroes have foundered. Only an active agent who risks his life for the sake of others can be a hero. But what is it that moves him to do that? Even though society may well benefit from his action, it does not stem from altruism, which subordinates one’s own interests to those of other people, but paradoxically from a motive that is almost diametrically opposed to altruism. The hero is very much present in his own persona, selfless but at one with his own ego, focused on the first person and its creative achievements. His heroics let him indulge his narcissism to an extent that would cause problems in any normal situation. When not performing dramatic feats, the hero often appears »antisocial« and displays a self-sufficient indifference to those around him – another aspect of his behaviour that only ratchets up his magnetism. Opting for active engagement is a lonely decision that owes more to his own personality than to the cause juste. His scorn for hazard can be attributed less to naiveté than to his outsized narcissism, which informs his idiosyncratic relation to reality. The hero’s »blindness to the world around him« is at once a carapace and a source of vulnerability. [Literature is peppered with subterfuges to explain this phenomenon: a cloak of invisibility, a special weapon, among other devices. The hero’s strength or weakness is determined by his level of access to these assets.]

The quest for a way to describe, in one word, this mélange of »greatness« and »unattainability« brings us necessarily to the aesthetic class of »grandeur«.

A man who is brave enough to suppress his instinct for self-preservation may well be capable – if he so chooses – of going further. The hero risks his skin for the good of the community, which in turn risks seeing the hero enlarging the scope of his power once he has acquired it. Spurred on by his enthusiasm and the pathos of his mission, he infringes those social rules and boundaries that a »non-hero«, likewise for the good of the community, is bound to respect. We cannot imagine a hero devoid of a narcissistic streak and the associated risk attached to wanting to expand the limits of his own splendour. It is precisely this fallibility that he has in common with the rest of humanity, and his special status among men is all the more glorious for it. It helps us to identify with him while he radiates in the sheen of his own enormity.

When he is defeated, the hero experiences a paradoxical intensification of glory. Not until he fails tragically does he achieve immortality. His downfall is lonely and »his own fault«, rooted in his voluntary exposure to challenges that he can no longer measure up to. He meets his end either in the fray or – not uncommonly – as a result of cowardly betrayal. In any case, he pays for failure with his life. Once dead, there is no limit to the fame he can achieve. To a certain extent his death is no »misfortune« as such but rather a social necessity, as it is the only way for a balance to be restored between human and superhuman activity. A moment of »catharsis« is reached, because a community can tolerate a hero only on a temporary basis.

Life in the post-heroic age

Our heightened awareness – stemming from historical experience of the risks inherent in heroism for both hero and society – can be evinced, for example, from the advice handed out by police and from attempts to supplant the ‘have a go’ urge with the concept of moral courage. How should modern burghers respond in a dangerous situation? In an initiative called »Do the right thing – but don’t play the hero« the German police have drawn up a set of practical guidelines on how to provide useful help without putting oneself in danger. The expression »playing the hero« has a pejorative connotation despite the apparently insuppressible desire to show oneself to be heroic, autonomous and capable of extraordinary feats. Nowadays there are few opportunities to satisfy that urge in real life, but the culture of heroism and victory lives on in fiction, in popular literature, in films and computer games and even in human role plays. The combination of an increasing sense of helplessness and [existential] worries that seem to be deepening with time provides the perfect breeding ground for a yearning for deliverance that is rooted in the Western Christian tradition. Searching for – and perhaps even finding – deliverance in a world view that undermines established, Christian ways of viewing the world and sees our empowerment and definitive liberation as being in the gift of ordinary individuals rather than a redeemer-type figure has even less allure than the deep-seated idea of a paradisiac state brought about in a final act of liberation by a flesh-and-blood saviour.

Each successive age is defined through the lens of its own specific ideals and social structures. At the same time it creates a climate that fosters a desire for virtues and constellations that are not currently in demand and which are often in downright contrast to what is considered proper. This means that in »post-heroic« times, too, we can find ourselves paying casual attention to people with heroic potential in the form of strength, courage, charisma and talent, as a way of tackling – or even solving – problems that appear insuperable. Barack Obama, who inspires a higher degree of interest and enthusiasm than would be explained by his office alone, seems a suitable candidate for the vacant position of Political Hero [»Yes, we can!«]. He is the centripetal focus for a bundle of societal desires and yearnings in search of a champion.

The rediscovery of Cola di Rienzo in the 19th century

The biography of the people’s tribune Cola di Rienzo – albeit with fictional additions – served a similar purpose in the 19th century. The English writer Edward Bulwer-Lytton [1803 - 1873] was not the first to draw on the life of this chequered character from the Early Renaissance period, but his novel Rienzi, or The Last of the Tribunes [1835] [translated into German one year later] clearly succeeded in compressing some of the core conflicts of the time into a historical novel, because it was the inspiration for a rash of later works based on the Cola di Rienzo story.

This novel by the author known for his The Last Days of Pompeii [1834] served Richard Wagner as a basis for his opera. It is not recorded if Wagner was also familiar with Rienzi: A Tragedy by another English author, Mary Mitford [1787 - 1855].

Posterity is divided in its appraisal of the achievements of the politician who rose from the obscurity of the petty bourgeoisie before failing magnificently in his life’s work.

Was Cola di Rienzo, in his urge to restore Rome to its former greatness, a visionary, an idealist, a pioneer of early humanist thought – and one far ahead of his time - who ran up against political reality and the unpredictability of the public and lost? Or was he a megalomaniac tyrant, who abused the ideas of Roman antiquity for his own power and glory and harnessed its iconography as a propagandistic accompaniment? 700 years after the events took place it is hard to establish the part played by his idiosyncratic personality, by a self-confidence that may have been wildly inflated by the success and supreme power that he had achieved. With the luxury of our modern-day perspective, we can doubtless attribute Rienzi’s failure to a string of political errors: the notion of uniting Italy under the sway of Rome; the limitless supra-regional power that he wished for on behalf of Rome; his misapprehension of the fact that the people had conferred the powers of state upon him irrevocably; and his underestimation of the extent of the reactionary powers pitted against him in the form of aristocracy and Church.

Rienzi as an identifier for national and republican movements

500 years after his death Rome’s multi-faceted popular hero from the 14th century experiences a rebirth. Cola di Rienzo, or »Rienzi«, gets the fictional, literary, historiographical treatment. Despite his ultimate failure, he is perfectly suited as a personage that people can relate to at a time of revolutionary national and republican movements, which were dominating oppositional politics in the first half of the 19th century.

Enter Richard Wagner, a staunch proponent of a revolution that was not only to shake up politics and society in general but also enabled the emergence of »a new, true art«. As a campaigner of yore, Cola di Rienzo could be enlisted in the name of each one of these revolutionary demands, meaning that the ongoing political situation could be observed and structured with reference to not one but two chapters in history: the achievements of Rienzo in the 14th century and – by extension – of ancient Rome.

So the story of Cola di Rienzo had everything to recommend it as a literary subject enjoying a second wind in 19th-century Germany.

Friedrich Engels, too, whose formative years covered the period leading up to the 1848 revolutions and who went on to champion the rights of the bourgeoisie and agitate for a radicalisation of revolutionary thinking, draws on the Rienzi material. In his dramatic fragment written as a 20-year-old in 1840 [probably as an opera libretto for his friend, the composer Gustav Heuser, and when he was still using the pseudonym Friedrich Oswald], his interpretation of events differs from that of mainstream opinion: Engels is interested in the fall of the tribune and reveals Rienzi’s thirst for power and opportunism for what they are; he views Rienzi not as a hero but as a man who betrays his people. In Engels’s eyes it was the people themselves who were the purveyors of progressive ideas. His spokesman, Battista, holds that neither »despots« [the traditional aristocracy] nor »tyrants« [Rienzi, the people’s tribune] are in a position to sweep away the injustice inherent in the social and political system:

First chorus

All hail to the Tribune, liberator of the people.

Who dares to mock him?

Second chorus

Down with him!

Battista

He is so bad, he is so good,

as all those men of noble blood.

He speaketh words so fine and clear

And lends the folk his open ear.

Tyrants out, a despot crowned…

Dogs have given way to hound.

.

The opera of Richard Wagners

Early on, during the adaptation of Bulwer’s novel, the 26-year-old Wagner is already showing himself to be a man of drive and solid theatrical instinct, with a clear vision of what he wants from his opera. He sees the grand opéra format, so popular in France, as his path to a triumph, and his adaptation of the material dovetailed perfectly with the form and structure of a grand opéra: the symmetry of the five acts with the rise-and-fall dramaturgy including a crisis in Act 3, the reversal of fortunes, the monumental Roman architecture, the weighty political aspiration, the scope for depicting the relation between individual and the masses. The unity of form and narrative is immediately apparent.

By the time his RIENZI premiered in Dresden, Wagner already saw himself as having moved on. With THE FLYING DUTCHMAN, the development of which partly overlapped with the making of RIENZI, he is announcing his interest in a new type of hero. The Dutchman swings between violence and devotion, split and estranged, disillusioned with people, a sad, restless, shelterless god. The contours of the Dutchman’s character – death wish, destructiveness, a desire for deliverance – are partly prefigured in the character of Rienzi.

The 19th century brought forth a new type of hero, a kind of »antihero« reflecting the bourgeois, split-personality individual: broken, suffering and incapacitated. Stubbornly clinging to his position, he foregoes happiness and contentment. This unsettled-hero variant still dominates our image of the protagonists in contemporary art, yet the positive hero corresponding to the traditional idea of the hero does not vanish completely from the firmament of the imagination. In mid-century he shifts primarily to trivial literature, a genre where he has ruled ever since. The edifying, ideology-based literature of totalitarian political systems, too, continues to use this heroic model, and the freshly hatched nation state spent a lengthy period of time viewing a heroic death on the field of battle as the purest expression of patriotism and seeing hero worship as the only way to trump military reality with myth.

The way in which Wagner soon comes to distance himself from his fourth opera bespeaks a self-assured and uninhibited outlook on his future work. In his Mitteilungen an meine Freunde he makes it plain that he is aware that his artistic objectives have evolved markedly from what they were at the time of RIENZI – and that he has also come closer to achieving them. The artists charged with the task of performing the work found it impossible to keep pace. The day after the world premiere in Dresden Wagner was already suggesting drastic cuts to the singers and musicians, who rebelled at the demands being made of them at rehearsals.

Hitler instrumentalises Wagner

Wagner’s own assessment notwithstanding, this early work – which also offers glimpses of Wagner’s future development - is a worthy focus of interest. With RIENZI Wagner pulled off an »archetypical« and parable-esque story about the rise and fall of a hero who is increasingly lonely and dares to push through major changes on behalf of the people, upholding the principles of justice, equality and peace. His destiny is to fail spectacularly, an end that is dramaturgically necessary for the rounding off of a hero’s biography. Beyond this, the downfall of the real-life Cola can be traced to his faulty gauging of political reality, his unbridled desire for power and his weak alliance with a Janus-faced people that remains unpredictable.

By choosing a pop hero of the 19th century as his protagonist, Wagner is following a standard pattern of narratives that feature mythical heroism. In grand opéra he has found a form that gives the freest possible rein to the material. This stratagem is complemented by the music, which allows audiences not only to identify with the eponymous hero but also to sit back and surrender to his promise of deliverance. Wagner’s dramatic instinct has not failed him here.

And the impact was also felt by the young Adolf Hitler, who was deeply affected by the work when he attended a performance in Linz in 1905. The details of how and whence he sourced the various components of his political ideology, cobbling them together like children’s building blocks, come over as frighteningly banal. During his early years in Linz and afterwards in his formative years in Vienna he absorbed political, ideological, pseudo-religious and pseudo-scientific experiences and moulded them into a kind of syncretic, political religion. They would form the basis for his pursuit of his stupendous – but still dormant – political ambitions. RIENZI, this much is certain, plays a key role in all this. Action and musical form alike are instrumentalised by him as a form of hagiographic folio. It is not long before the piece has established itself at the core of national socialist propaganda and myth-mongering. It functions as a parable of Hitler’s political rise and legitimises his form of government and the way he exercises power.

Hitler was in raptures after seeing the opera and gushed to his friend August Kubizek about it: »In a succession of amazing set pieces he [Rienzi] unveiled the future of the German people to me.« Hitler would later refer to the performance of RIENZI in Linz as his seminal experience. [»That was the moment it all started«]

Once again, the opera has got people identifying with the Rienzi character. The message of the new heroes of the early 20th century is [pseudo-]religious and [pseudo-]scientific. Wagner’s opulent rendition of the material leaves a lot of space for private projections, and both readings are possible: Rienzi’s overtly intimate, almost physical relation to God [»God, who used me as a channel for his miracles«] on the one hand; and the idea of a science-based eschatology on the other, which takes the »objectively« measurable state of a people to be an indicator of the overall condition of that society – the collective noun »people« being used here in the sense of a group of »politically minded persons« acting as one and whose actions are shapeable. The idea is that a charismatic populist can lead the people out of a state of »degeneration« to a state of [antique] »greatness«. As Rienzi prophesises to the Romans, »May a new people arise within [Rome], great and noble as its forebears!« Hitler has similar plans for the German people.

During the period of the Third Reich music, and opera in particular, becomes a sensuous and manipulative tool of pseudo-religious suggestion for the masses, smoothing the way for individuals to identify on an emotional level with the objectives of the people’s champion. »Getting people to believe is the specific role of a great leader.« [Gustave Le Bon] And with RIENZI Hitler has the perfect tool. Reinhold Hanisch, Hitler’s mate from his time at the male hostel in Vienna, describes his fellow resident: »He was very taken with Wagner and sometimes said that opera was the best form of church service there is.« Hitler adopts some of the terms used by Wagner [»Heil Rienzi!«] and some of his staging ideas for grand rallies and mass rituals. The RIENZI overture becomes the unofficial anthem of the Third Reich and part of its liturgy. It remains hugely popular to this day and provides the theme music to the »Spiegel-TV« programme. Statements by Hitler suggest that he sees himself as the physical reincarnation of Cola di Rienzo. Like Wagner’s Rienzi and the original historical personage, he embraces Roman symbols and iconography and the monumentality of the ancient world.

A new type of politician, the »people’s tribune«, had already made its entrance on the political stage in the Vienna of the early 20th century. The term was no longer associated with an actual political office; it denoted a paradigm shift in a politician’s outward appearance and public comportment. The new stars in Vienna’s political firmament, men like the leader of the German Nationalists and later head of the Pan-German Union, Georg von Schönerer [1842 - 1921], and the Mayor of Vienna, Dr. Karl Lueger [1844 - 1910], were populists and perfect exemplars of this new breed. They were quite unlike the liberal, educated »tutor« types that had dominated the scene hitherto; gone was the elitist gulf between the instructor and the instructed. The new breed of leader cultivated links to the »ordinary man« in taverns, beer halls and marketplaces. Benefiting from this ostensible proximity to the common man, they had their finger on the pulse »of the people« and offered assistance, making simple and unambiguous demands in return. In their speeches they appealed to the feelings and instincts of the people rather than to their reason. The concept of the »people’s tribune« was a touchstone between the present day and the salvation myth represented by Cola di Rienzo and his evocation of the Roman Republic – and co-opted by Hitler for his political purposes.

Politics of the apocalypse

So it is that, by dint of its reception during the first decades, RIENZI has come to be linked to the theme of fascism, to an extent that people need to position themselves and comment. There has never been a period when art was not misused for partisan purposes, but rarely has a single politician identified so strongly with a fictional character and been so adept at modelling his own biography on the fortunes and demise of that character. One feature that the trajectories of Rienzi and Hitler have in common is their expectation of eschatological salvation. This way of framing and narrating reality emerged in the early years of Christianity and can be traced back to ancient times. It has been the dominant narrative pattern in many of our tales and myths right up to the present day. When applied in the fields of politics and religion it takes a disturbing turn.

Christ and his followers lived in full awareness that an end of days would come. They were convinced that it would be followed by the birth of a new and better world. In the absence of the Day of Judgement it fell to the heroic Jesus Christ to redeem humanity with his death on the Cross.

This doctrine is founded on a number of components that formed, and continue to form, not only Christianity but also a raft of very different and largely non-Western world views. The first of these components is the idea that the history of mankind has a purpose – the salvation of humanity – and unfolds on a linear timeline, with a foreseeable end. A second component has progressive thinking linked to a radically dualistic world view, involving a clear division into Good and Evil. Thirdly, before the dawn of this new age there is a »final battle« to be fought and Evil to be defeated once and for all. Fourthly, the apocalypse [literally: »revelation«] presents as a »tipping situation« and precedes the expected »better world«, separating the »good« people from the »bad«. For one group the apocalypse means salvation, for the other ruin.

When a heavenly age in the Christianity of the first generation proved a little slower in arriving than expected, this did not have the effect of overturning people’s convictions; their perspective on the end of the world simply lived on as an equation on an abstract level. Western imagination is still informed by this visionary, apocalyptic thinking. It is not hard to fathom why a narrative like this, whose second part - Paradise, Jerusalem, whatever label you choose to put on it – has still not come to pass, managed to acquire such suggestive power: it goes a long way to satisfying man’s need for a meaning to life. A belief in progress gives people courage and gives their lives meaning and orientation.

And so it was that a momentous notion across the Western world came to hold interpretative sway. It expanded from religious into secular ideologies. Every revolution or revolutionary movement is predicated on the possibility of a sudden turnaround that, once brought about, would be in a position to erase the mistakes of an entire society by striking a liberating blow. The utopias of the modern era, such as communism or national socialism, are a precise reflection of the procedural and presumed thought patterns founded on apocalyptic visions. Politics and war become tools for asserting a country’s mythologies around the globe. Up till now, however, each utopia has managed to achieve the exact opposite of what it claimed to be aiming for. Much more serious than their failure, though, is the fact that utopias acquire an unequalled degree of violence on the path to paradise.

The fact that the dramaturgy of our hero narratives is rooted in Christian thinking based on apocalyptic visions makes its conversion from fiction to reality dangerous. As an »injury« to humankind, the myth cannot be magicked away, but it can still play a role – as a fantastical, abstract narrative with scant relation to real life or as a negative utopic vision of society in a present-day narrative tradition. One might well ask: which alternative or additional patterns of interpretation and narration could also gain currency as political or present-day social models. To identify these patterns, we must bid farewell to the notion that human history is a coherent whole and is following a predetermined pattern of historical evolution. The conception of the course of human history as an aimlessly meandering river would be an alternative notion, free of heroes, in which questions about the meaning of life have to be resolved by each person individually rather than answered collectively.