Jetzt spielen wir! - Deutsche Oper Berlin

Now we’re playing!

Detlev Glanert's DIE DREI RÄTSEL (THE THREE RIDDLES) is a children's opera that is anything but cuddly. And here, the children don't just sit in the stalls; they play along – in the orchestra pit and on the stage.

A dark wine cellar in the afternoon. A faint glow falls on large wooden barrels, an old table and crooked benches. People are milling around, some standing, others sitting on barrels or crouching on the floor. And in the middle of it all: a boy on a wooden crate, unkemptly dressed. His name is Lasso, he is the son of the landlady Popa, and he is anything but quiet. Together with his friends, he is part of the noisy group, but what began as convivial drinking has long since turned into an argument. The adults are swearing, Lasso intervenes. He is shouted at, countered with ridicule, accused, and accused in return. He is said to have peed on the town hall. It is a jumble of accusations, noise, and alcohol, a scene between the grotesque and the comedic, and it ends in a scandal. Popa returns, throws the guests out, and confronts her son. And what does he do? He simply disappears. Not quietly, but defiantly. He declares the adults incompetent and leaves.

This is how DIE DREI RÄTSEL begins, Detlev Glanert's opera for children and adults – with a departure that is not solemn, but rather grandiose. And with music that doesn't hesitate for a moment. "In the very first scene, Glanert really throws everything he's got into it. It gets off to a powerful start," says director Brigitte Dethier, the grande dame of German children's and youth theater and long-time director of the Junges Ensemble Stuttgart. The opening is an orchestral tutti, loud, dense, exuberant. Not a gentle glide, but a musical impact with a powerful pull. And it’s immediately apparent that it's not just children who get their money's worth here. Glanert succeeds in creating a work that touches children and adults in very different, yet equal, ways.

What follows is a fairy tale full of strange characters and absurd twists and turns. Lasso ends up in the Murder Forest, where a gang of robbers ties him up and plans to hang him. At the very last moment, salvation falls from a tree: a suicidal, melancholic man with a rope around his neck, who calls himself the Hangman. He becomes Lasso's companion, grumpy, loyal, a kind of anti-heroic sidekick with a heart. Together they set off for a castle where the young Princess Scharada is waiting for suitors, each of whom must ask her three riddles. Whoever formulates the riddle in such a way that Scharada cannot solve it wins her hand. Whoever fails loses their head.

Opera lovers immediately think of Puccini's TURANDOT. And indeed, both Carlo Pasquini, the librettist of DIE DREI RÄTSEL, and Carlo Gozzi, whose story Puccini's opera is based on, draw on the same 13th-century fairy tale collections. The basic structure is always the same: Someone must go out into the world, solve tasks, prove themselves or, in the best case, both. The story is enriched with literary archetypes. The robber with the beard, the fat-bellied king with the crown, all familiar figures. "Children need clear social affiliations," says Glanert. "The postman needs his cap. The king his crown. Only when this world is coherent on stage can one play with it."

But where in TURANDOT the riddle appears as a power play of the unapproachable, here it is about something else: the attempt of two young people, Lasso and Princess Scharada, to assert themselves against the demands of a rigid adult world. "I'm interested in the question of how two characters from very different backgrounds meet," says Brigitte Dethier. "Neither have functional parental homes, both feel abandoned. And it is precisely from this that they develop a form of closeness." Carlo Pasquini's libretto strikes a balance between fairy tale and social parable. The scenes are episodic, the characters often exaggerated, and yet beneath the grotesque lies a psychological seriousness. "You should never believe that characters can be superficial for children. They notice that immediately. They have a very fine sense of whether something is real," Dethier explains. This authenticity is the central criterion for Dethier's work, also with regard to the question of what one can expect children to endure. "You can expect a lot from them – as long as there's hope. The story can be crude, even a bit coarse in places, but it has to offer children someone they can root for. If you're warmly welcomed, then it's okay to take your breath away or be speechless for a moment."

The fact that the opera doesn't appear smooth on stage, but deliberately polyphonic and polystylistic, is also a result of its creation. DIE DREI RÄTSEL were originally written for the Halle Opera House and the Cantiere Internazionale d'Arte in Montepulciano, the summer academy founded by composer Hans Werner Henze, which has been a model for intergenerational, collaborative music-making since the 1970s. Professionals, amateurs, children, young people and adults all perform together on stage. For Henze student Detlev Glanert, Montepulciano was a formative place. "The summers there fundamentally changed my understanding of music education," he says. "Artistic learning happens through doing. And even more importantly: Learning a musical instrument alone is basically pointless. You always have to play with others right away, in different ensembles, however it works. The togetherness is what matters, not the isolated element. The playing comes naturally."

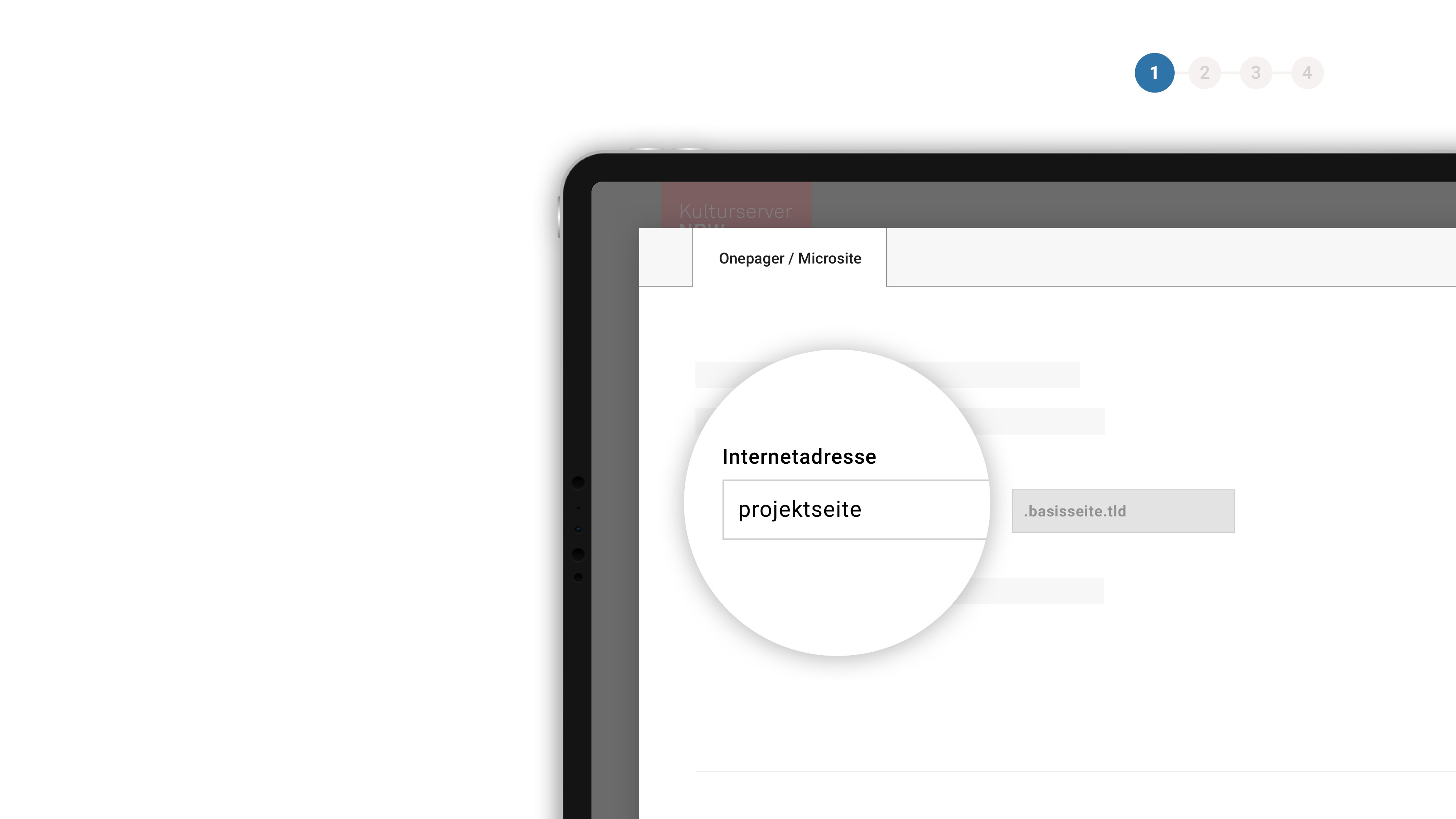

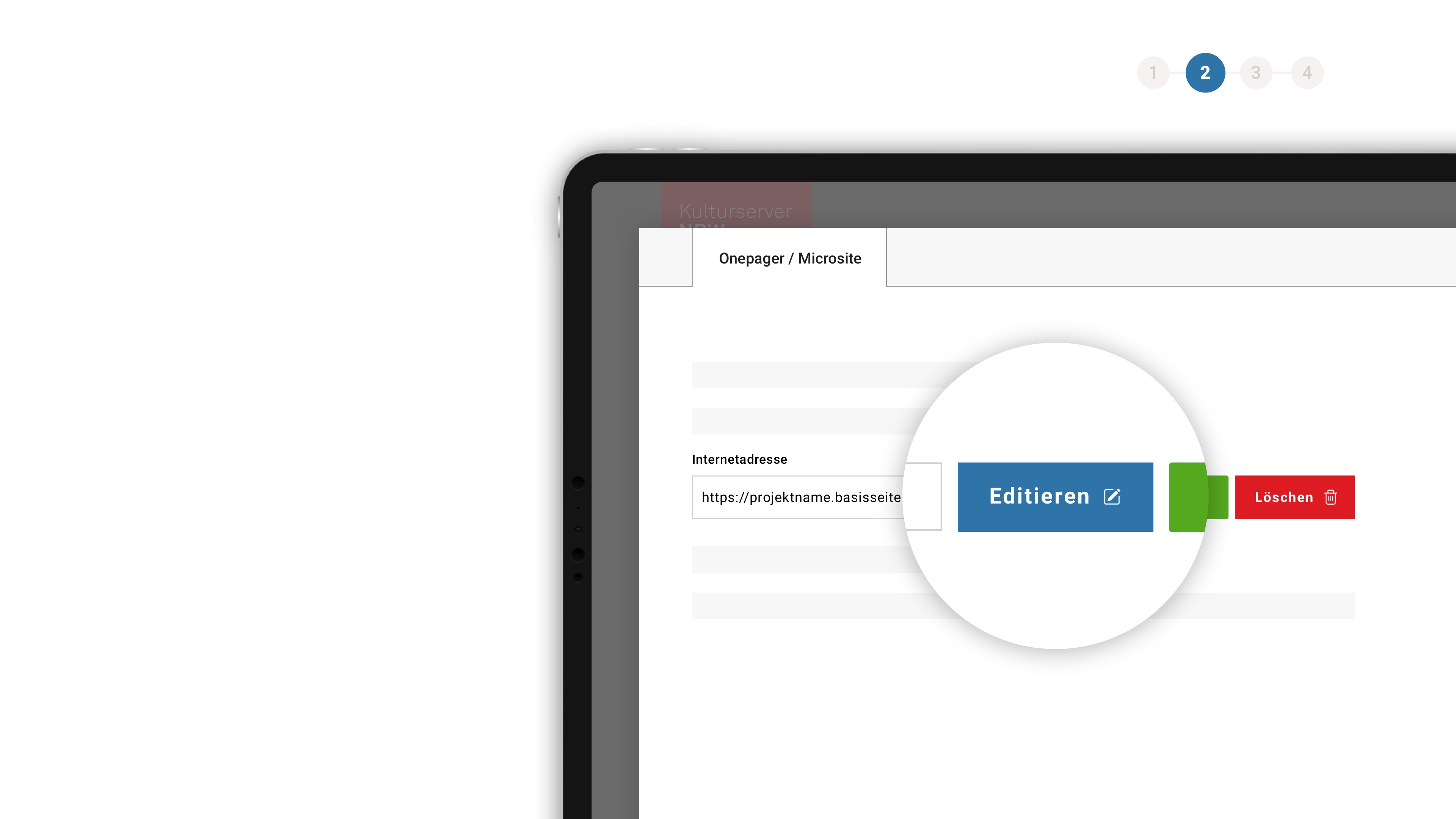

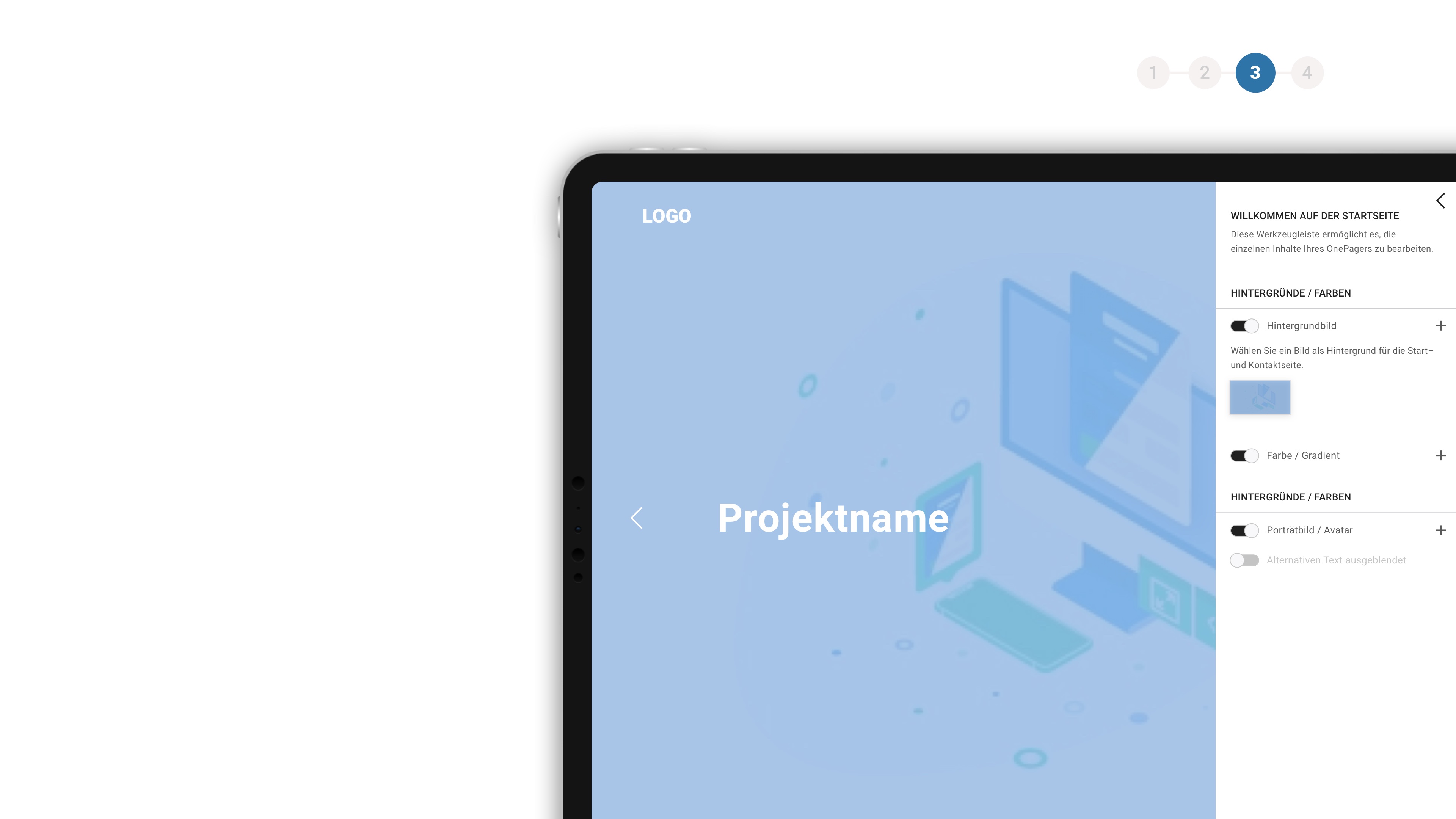

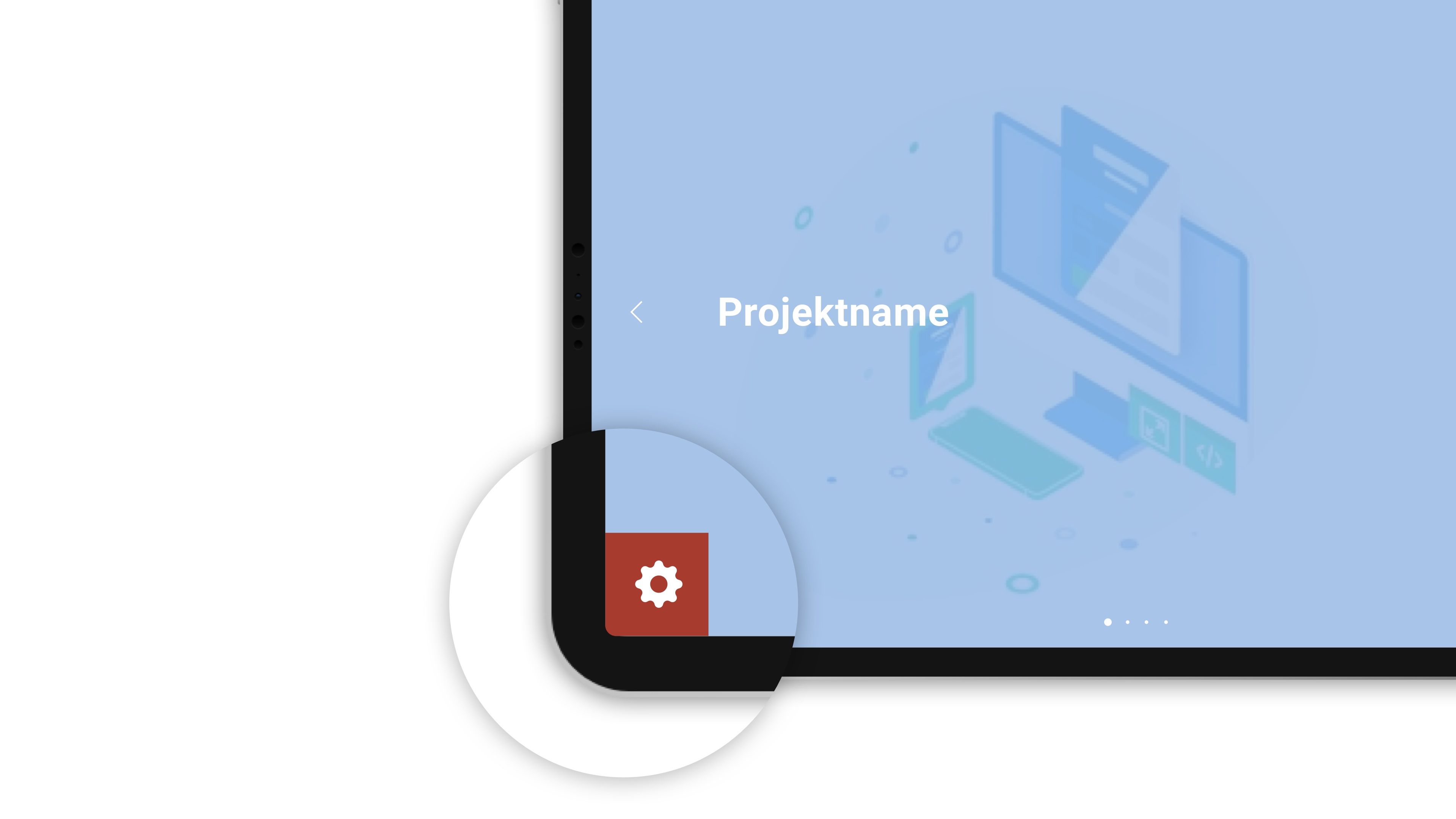

Glanert's score consistently follows this idea: It has a modular structure, contains parts of varying difficulty, and can be scaled to suit the venue. In Berlin, the orchestra will be larger than in Montepulciano; even a tuba part has been specially added because a talented young tubist wanted to join in. There are also simple string parts that can be played by children with only basic fingering skills. A total of over 40 children and young people will be sitting in the orchestra pit. "Anyone who wants to play and sing along should do so," says Glanert. But they have to put in the effort and will be challenged. Before the performance, there is an intensive rehearsal phase in which the children and young people can learn a lot from the professionals. "They have to learn what form is. Why does a musical motif repeat itself? Why doesn't something else repeat itself? But also very banal things, like going to the bathroom before the acts – a very important point." And what do the adults learn from the children? "The adults learn humility again in the face of what they do. And they do so through the sacred seriousness with which the children approach their work; for them, for a moment, it becomes the center of their existence. For a seasoned professional, this is an incredibly important lesson," says Glanert.

And yet the result doesn't sound didactic. DIE DREI RÄTSEL isn't music for pedagogues, but a serious work of musical theater with stylistic complexity, oscillating between symphonic power and subtle irony. The composer quotes, counters, plays with formulas – and yet remains clear. "I want to show children how much music can do," he says. "Not in the sense of: I'll explain to you how it's done. But rather: I take you seriously. And I know that you hear everything."

It's clear that Glanert draws on a rich breadth of creative experience for this. In conversation, he repeatedly refers to his own youth: to playing in the Hamburg Youth Orchestra, to his encounter with Strauss's SALOME, which deeply impressed him at 16, to his childhood fascination with musical drama. Perhaps this is also why Lasso isn't an idealised child figure, but rather a nonconformist, overwhelmed, yet simultaneously touching boy on a quest. For Glanert, it is a mirror of youthful self-assertion, a pubertal disorder in the best sense: uncomfortable, loud, necessary.

The stage design is also loud, at least in a figurative sense. Brigitte Dethier and her set designer Carolin Mittler don't want to smooth over the grotesque, but rather make it visible. In their production, they value atmospheric contrasts. A giant chair that transforms into a guillotine. Dark cellars, shimmering fantasy worlds. But Dethier is never just concerned with grand gestures, but with psychological depth, with characters who are intended to be serious and taken seriously. "I want to give children something with which they can think for themselves," she says. That's why she also rehearses specifically with individual groups. "We sometimes hold our own rehearsals just with the young people. Without pressure. Without professionals. So they can ask their questions."

The result is an opera that is equally enjoyable for adults and children – and works on both levels. It is an effect perhaps most subtly demonstrated by the famous US cartoon series The Simpsons: The little ones laugh at the situational comedy, the adults at the subtle social critique. Dethier speaks of an "experience in which children and parents can exchange ideas afterward, discussing their very different perspectives." And what else remains after the performance? First: an earthquake. Announced in the libretto by windy omens, musically prepared by a crescendo lasting 15 minutes. "The biggest thing in the piece," says Glanert. "It begins very quietly – and ends with a bang." But the opera also resonates emotionally. Dethier sums it up: "I wish that adults would go out and ask themselves: What kind of world do we actually live in with our children? And what can we do better?" For the children, in turn: five centimetres more backbone. "If Lasso and Scharada can do it, then so can we." – Text: Tilman Mühlenberg

Milla Luisa Dell'Anna and Jonathan Betzold play and sing the main characters Scharada and Lasso. Read what they told us about their roles here

Milla Luisa Dell'Anna, 12 years old, on her role of Princess Scharada: "At the beginning of the story, Scharada is very grumpy and a little snooty – but by the end, she's actually a really nice girl. I like that we get to know her slowly. I think she's too stubborn to guess the correct answers to Lasso's riddles; she doesn't think properly and immediately shouts, that's cheating!" My favourite part of the entire opera is the final chorus, when Hangman has found his new home in the shell, and we all sing De de de di du, ba be bi bo bu. It's simply beautiful and a really great ending, too."

Jonathan Betzold, 12, on his role of the innkeeper's son and fortune-seeker Lasso: "I think Lasso is really cool. In some situations, I feel just like him—not necessarily like at the beginning, when he's sitting in the wine cellar smoking; I wouldn't do that. But when he's desperately crying for help in the Murderer's Forest, I really feel it myself in that moment. Lasso is the same age as me, so it's pretty brave to just set off on his own. My most difficult part is when I'm in the boat with Hangman on the way to the castle, and we take turns singing. Getting the cues right is really complicated. But I'm sure I'll get it sorted by the premiere."

The orchestra includes many young musicians from the State Youth Orchestra, the Arndt-Gymnasium Dahlem and the Musikschule City West. We interviewed three of these young musicians for you.

Penelope Zybell, 14, violin: "I've been playing the violin since I was five. Sometimes it was tough, but sticking with it was definitely worth it. I only moved to Berlin last summer, and the school orchestra helped me quickly find my place. I prefer playing in an orchestra to playing solo anyway, because you make music together. You're not alone in the spotlight, but create something beautiful together. At Glanert's opera, I'm looking forward to the huge stage, the orchestra pit and meeting lots of new people. Stage fright? Never in an orchestra—there I'm part of a whole. And if I make a mistake, my neighbour on the podium looks over at me and grins."

Nicolas Reinholz, 17, baritone saxophone: "I play the baritone saxophone. This large, somewhat niche instrument has its own appeal. I like that there are few people who play it really well, so you have room to develop your own sound. I'm in the BigBand and the upper school orchestra at Arndt-Gymnasium, which our music teacher Dr Burggaller has led with incredible dedication for decades. In DIE DREI RÄTSEL, I'm fascinated by the combination of classical and contemporary music—with time signature changes and expanded playing techniques. I'm interested in new music anyway: As soon as you think everything has been said musically, something completely different comes along."

Jaron Melle, 17, trumpet: "I've been playing the trumpet for eleven years. I'm fascinated by the fact that the trumpet has a permanent place in all styles and eras. Personally, I prefer late Romantic works. We recently had a Mahler phase in the Berlin State Youth Orchestra, and I've been listening to it on repeat. I've already performed with the orchestra in the Konzerthaus and in the large broadcasting hall of the RBB, and this fall we'll be playing at the Philharmonie. DIE DREI RÄTSEL will be something special for me: We'll be sitting in the pit with the professional orchestra. I'm not really that nervous anymore. Although... I recently had to open a concert with a solo fanfare, and it did get my pulse racing."