Leidenschaft und Kalkül - Deutsche Oper Berlin

From the programme booklet

Passion and Calculation

An Essay by Kadja Grönke

When Alexander Pushkin published his story “The Queen of Spades” in 1834, prose was not highly regarded in Russia. To Pushkin’s contemporaries, it was hard to understand why the acclaimed Russian poet abandoned the sublime heights of his poetry to descend to the depths of everyday vernacular. At the time, sophisticated literature was synonymous with verse – or at least with opulent rhetorical effort. A good three decades before Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky began writing their great novels of psychological depth, in “The Queen of Spades”, Pushkin wove a net of relationships and allusions, recounting in provocative brevity the story of the officer and gambling addict Hermann and the poor orphan Lisaveta Ivanovna, blinded by her longing for love. Without detours or digressions, the author describes how the rumour that the old Countess supposedly knows the secret of three failsafe cards incites Hermann’s long-suppressed gambling addiction. When he happens to hear of the Countess’ poor foster daughter, he pretends to love her in order to learn the secret through the young woman. The Countess, however, dies before she can reveal the three cards; Lisaveta Ivanovna realizes that Herman has merely used her; Hermann gambles away all his money and ends up in an insane asylum; and the young woman quietly marries a well-behaved young man.

From Story to Opera Plot

What Pushkin sketches out from an ironic distance becomes a highly emotional experience of suffering in Tchaikovsky’s stage work. A small but significant indication for this reinterpretation is the name change of the female protagonist. Lisaveta Ivanovna becomes Lisa – a familiar, intimate form of address, but also the heroine of a widely-read story at the time: in 1792, the poet Nicolai Karamzin had created the epitome of a female heroine betrayed by her beloved and – literally – deadly unhappy in “Poor Liza”. By taking up her name, Tchaikovsky makes it clear from the start that a love meaning such a misalliance for his opera heroine can only end tragically, as it does in Karamzin’s tale: with Lisa’s suicide. Furthermore, Tchaikovsky’s Herman is no longer Pushkin’s: the spelling of his name is Russified, he loses the last letter – in Pushkin, the extra n in Hermann still pointed to the male protagonist’s German roots (which are relevant for the story’s leitmotifs, but irrelevant in the opera).

Why did Russia’s most renowned composer decide upon such a massive reinterpretation of Pushkin’s little prose piece in 1890? Lack of respect or even parodistic intentions can be excluded as motives. Tchaikovsky always took Pushkin seriously and venerated his writing. He did, however, interpret it in his own way and before the backdrop of his own life and loving. This made ironic distance impossible to him, no matter how much humour and distance Pushkin might have brought to his characters. Within only six weeks, between the end of January and the middle of March of 1890, Tchaikovsky wrote his extensive score in a veritable creative frenzy, and – at least outside the Slavic cultural sphere – it quickly pushed awareness of Pushkin’s underlying prose work far into the shadows.

How difficult the composer found it to maintain a distance from his characters is demonstrated by his regular comments in his letters on the composition process, particularly the role of Herman, which was intended for the tenor Nikolay Figner, whom Tchaikovsky held in particularly high esteem. “When I got to the death of Herman, I was so sorry for Hermann that I began to sob. […] As I had never sobbed over the fate of a hero of mine before, I tried to understand the reason for it. It appears that Herman was not just a subject about which to compose this or that music, but a real living person whom I liked. Because I like Figner, and because I keep imagining Herman to be like Figner, I sympathized most vividly with his fate,” the composer wrote to his brother and co-librettist on March 15, 1890. “I think,” he added laconically, “that this warm and vivid sympathy for the hero of my opera has presumably had a beneficial effect on the music. On the whole, the opera seems quite good to me at the moment.”

Love and Tragedy in Tchaikovsky’s Pushkin Operas

This emotionalizing and focus on love and tragedy is a logical continuation of the development Tchaikovsky already practiced in his earlier stage works based on Alexander Pushkin’s works. Before Tchaikovsky turned towards the prose work “The Queen of Spades” in 1890, he had already used the novel in verse “Eugene Onegin” as an opera plot, and composed his opera MAZEPPA based on Pushkin’s narrative poem “Poltava” in 1884. None of the three literary models was really destined for the musical theatre stage: Pushkin’s “Eugene Onegin” offers a multi-faceted “encyclopaedia of Russian life”, giving facetious and profound insights into the culture of Russian nobility during the post-Napoleonic era and Russian philosophy of life during the first third of the 19th century in the tone of so-called light poetry. The verse epic “Poltava” combines Russian history of the time of Peter the Great with reflections on power and its abuse, while the straightforward, intense brevity of the prose in “The Queen of Spades” hardly leaves room for a psychological description of the figures (which was not Pushkin’s intension anyway). In order to turn these literary texts meant for reading into convincing stage works, the composer had to intervene and define the focus of attention; and Tchaikovsky placed this focus on his lifelong theme: love – more specifically, the exclusive, overwhelming, but unfulfilled love of a woman for a man who does not respond to this love with the same exclusivity. This is not in contradiction to his feelings regarding Herman, but complements them, as THE QUEEN OF SPADES is the first time that an equal hero joins a female role in Tchaikovsky’s work – equal also in musical terms.

For his theme of love, in EUGENE ONEGIN the composer has to break down the complex timeline of the verse novel to the story of Tatjana, the country noblewoman, and Onegin, the metropolitan dandy – and no composer before or after him has ever said as much about a female soul’s process of maturing towards self-awareness. From Pushkin’s narrative poem “Poltava”, Tchaikovsky chose those passages in which young Maria falls for the old and power-hungry Mazeppa, leader of the Cossacks, and makes Maria the tragic heroine of his opera MAZEPPA. And in THE QUEEN OF SPADES, Tchaikovsky increases the height from which his Lisa falls by making Pushkin’s poor orphan not only a noblewoman, but also a rich and respected fiancée who is shortly to marry Prince Yeletsky. In addition, there simply is no such competing male figure in Pushkin’s story. Tchaikovsky, however, definitely needs this character to increase the urgency of the conflict.

Class Differences

For Lisa, it is the conflict between the marriage of duty – expected of her by society – to a man she respects and values on the one hand, and the abyss of her passion for the socially low-ranking Herman on the other. For Herman, her engagement to Yeletsky increases Lisa’s unattainability, which he believes he can only circumvent if he owns “mountains of gold” (as he fantasizes in the libretto). The fact that he simply ignores the fact of Lisa’s engagement is not only a sign of bad character: Tchaikovsky thereby shows that Herman’s all-consuming love may have been sparked by Lisa, but in truth it belongs to the legendary “golden mountains” – and does so until death.

The constellation in which Tchaikovsky’s Lisa finds herself is therefore quite different than in Pushkin: she loves a man who is not her social equal, loves him passionately and exclusively. However, she has the alternative to return to her fiancé at any time, who offers her an unselfish union which is focused entirely on her happiness and socially accepted. Tchaikovsky thereby reverts to the dramaturgical model of his earlier Pushkin operas: Tatjana too has an alternative to Eugene Onegin, and unlike Lisa, she decides to actually marry this alternative love, to bury her feelings for Onegin deep inside and become a respected Princess in St. Petersburg. To this end, Tchaikovsky turns Pushkin’s marginal figure of Tatjana’s nameless husband into the opera character of Prince Gremin, whose name transports meanings such as “resounding loudly”, “being praised”, “having a good sound”, and for whom he composes the only great aria in this opera. Similarly, Maria, the protagonist of MAZEPPA, was destined for the young, emotional Andrey, whom her parents consider much more suitable for her than the old, temperamental leader of the Cossacks. As in THE QUEEN OF SPADES, Maria – like Lisa – decides against the obvious, and in favour of a love which ultimately destroys her life.

Corpses, Ghosts and Visions

Before, however, just like in Tchaikovsky’s two other Pushkin operas, a person close to them must die: in MAZEPPA, Maria’s love choice ultimately leads to her father’s execution; in EUGENE ONEGIN, Tatjana inadvertently causes the duelling death of Lensky, her sister’s beloved; and in THE QUEEN OF SPADES, Lisa enables the death of the old Countess. For only because Lisa invites Herman to an assignation in her room, handing him the key, does he have the opportunity to sneak into the Countess’ boudoir, whereupon the old woman dies, frightened by the intruder, without having told him the three magical cards. Lisa’s horror upon discovering him and her dead grandmother fails to move Herman at this moment; he shows no trace of a guilty conscience. His desperation is caused only by the impossibility of wrestling the secret of the three cards from the deceased woman.

After this, Tchaikovsky composes what must be the most gripping ghost scene in opera history: alone with himself and his conscience, the extremely agitated Herman remembers the funeral of the old Countess, and – is it a delusion of madness or a dream? – experiences sheer horror when her ghost appears to him. As befits operatic ghosts of the romantic era, the Countess’ ghost recites its lines on one note, giving Herman what his subconscious demands: the identity of the magic cards, Three, Seven and Ace. The Countess (or Herman’s subconscious) makes his winning at the gaming tables conditional upon his marrying Lisa. Herman’s overwrought mind, however, only has room for the secret of the cards. His perception ignores the condition tied to the cards. On his way to the casino, he encounters Lisa, but no longer recognizes her, so obsessed is he with the thought of the “mountains of gold” he believes will imminently be his. Indeed, he wins with the Three and the Seven. In the third, all-important round, however, which Tchaikovsky heightens further by making it a card duel between the adversaries Herman and Yeletsky, Herman inadvertently bets not on the Ace, but on the Queen of Spades. Herman believes that he sees the likeness of the old Countess in the card, and takes his own life. Before his death, however, he sings a moving declaration of love for Lisa – in which he addresses his “goddess”, his “angel” by her actual name for the first time in the entire libretto. What he cannot know, however, is that Lisa, feeling guilty about the Countess’ death and Herman’s delusion, has already drowned herself in utter desperation. The tally is three corpses in Tchaikovsky, compared to one in Pushkin.

On the Score for THE QUEEN OF SPADES

The opera’s music is a fascinating mixture of passionate emotionality and compositional calculation. Herman’s desire starts blossoming forth at the end of the short orchestral prelude: in six waves, played by an overwhelmingly harmonious string section “molto espressivo” and growing from soft to loud, this melody strives towards a resplendent climax, only to fade in an expansive line. How could Lisa escape the emotional impact of this feeling?

The orchestral prelude tells the audience everything it initially needs to know about Herman: it speaks of an absolute, unlimited and irresistible love and passion. But what is the object of this powerful feeling?

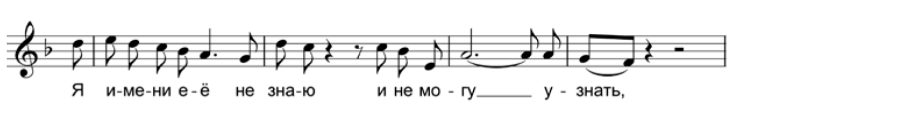

When Herman appears on stage for the first time, he confesses to his friend Tomsky that he is in love. This love, however, tortures him, because it seems hopeless to him due to the class differences. He adores Lisa only from afar, and at this point he doesn’t even know her name:

The music here is reminiscent of the passionate desire evoked by the orchestral prelude – but without its first, hopeful, ascending phrase. It consists only of an expansive falling line, whose length seems to reflect the overflow of this love’s desire, and whose descent also emphasizes the unfulfillable nature of this longing. This melody is combined with brief gestures of sighing. – Is Herman really in love with Lisa, or perhaps rather with the hopelessness of his love? Tchaikovsky’s music does not provide an answer.

The illusion of love has a strong counterargument: everything that is fatal about the stage action unfolds from one motif – employed instrumentally for the most part – which is firmly associated with the old Countess. It consists of three rhythmic groups of three notes in the anapaest rhythm of short-short-long, all striving towards a final note. This last, accented final note on which the motif ends – just as the wrongly drawn card ultimately ends Herman’s life – is initially missing. The motif sometimes appears as a rigidly repeated figure, or it gradually winds upwards (like the beginning of the melody of desire). Musically, fate and passion are thereby closely linked.

The incisive way in which Tchaikovsky deploys the motif of fate (in the manner of a true master of stage dramaturgy) is demonstrated immediately after Herman has confessed his secret love to his friends: his unhappy love clashes with Yeletsky’s joy at his engagement, and when Herman asks the Prince his bride’s name, Lisa appears with the old Countess, as if in answer to the question. At the same moment, however, the orchestra is not playing the music of passion, but – psychologically unfathomably – the old woman’s motif of fate. Herman recognizes here for the first time that the object of his adoration is engaged to another man; yet his subconscious perceives nothing but the old woman – and thus the keeper of the secret of the cards.

In an impressive tempest scene in which the breaking of the storm mirrors the tempest inside Herman’s soul, he vows to conquer Lisa. Since this only seems possible through social climbing, and the latter only via wealth, his oath implicitly also includes obtaining the secret of the cards – and this draws him towards the old Countess. She appears every time he is attracted to Lisa, and thus acquires an erotic appeal that is similar to Lisa’s. Tchaikovsky demonstrates this in two bedroom scenes: in Lisa’s bedroom in Act I, Herman is almost surprised by the Countess, which lends his courting the last drop of conviction. And in the Countess’ boudoir, where he hides himself in Act II instead of going to Lisa’s room, his struggle for the secret of the cards is no less filled with eros and passion than his previous courting of Lisa. In both scenes, moreover, love and death, Eros and Thanatos, are significantly linked: Herman blackmails Lisa into reciprocating his love by threatening suicide; and the death of the old Countess is a consequence of Herman’s passionate pleading, which, when the Countess does not answer, turns into a threat of murder, if he is rejected.

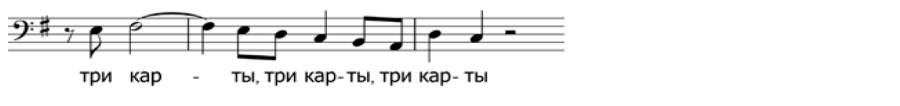

In the course of the opera, Herman’s passion is redirected in ever more obsessive ways from Lisa to the Countess, and thus from love to money. The spark and musical element that sets the dramatic ball rolling is Herman’s comrade Tomsky (as is the case in Pushkin’s literary model). He is the one who first mentions the secret of the cards: among his circle of friends, he recounts why the Countess is known as “the Queen of Spades”, and how she is said to have gotten hold of the secret of the three winning cards. Tchaikovsky turns this ballad into the musical centre of his opera score (in a similar way as Wagner treats Senta’s ballad in DER FLIEGENDE HOLLÄNDER): like an obsessive refrain, Herman keeps hearing the words “three cards, three cards, three cards” – a striking, rhythmical downward line with an accent on the final note.

The descending line also exists in Herman’s theme of adoring love, and the principle of rhythmic structuring it in three times three notes with a clearly accentuated final note is taken from the old Countess’ motif of fate. In this way, Tchaikovsky’s music reveals how inextricably passion, luck in gambling resp. hoped-for riches, and the old Countess are linked, merging into one in Herman’s fevered mind. Tchaikovsky’s score is composed around this ambivalence of Herman’s desire. Ultimately, it is not loving desire that dominates, but the riches he craves. His greed draws him away from Lisa and increasingly towards the Countess, whom he courts with almost passionate obsessiveness, torn between attraction and repulsion. This fixation on the old woman, who, to Herman, is the incarnation of winning at cards and his future riches, so to speak, is portrayed by Tchaikovsky in musical and dramaturgical terms almost like a clinical obsession. Herman’s downfall is painted for the audience’s eyes and ears with an increasingly precipitous fatality. In the end, love and death are only intermediate stops on his path towards the “mountains of gold” which Herman desires with all his might. When he fails to win them in the end and his love is lost, the only part of the trinity that remains for him is, indeed, death.

And yet, despite the sympathy with his male protagonist that Tchaikovsky expressed in letters and diary entries, Herman is not the only hero here. He may spark compassion and horror – as antique tragedy would demand. Tchaikovsky’s profound sympathy, however, belongs to Lisa’s unfulfillable longing for love, a longing that only ends in death. To make that perfectly clear, the composer invented the entire sixth scene, and thus the highly emotional last encounter by the canal, Herman’s rejection of Lisa, her pangs of conscience and her suicide, none of which exist in Pushkin’s story. Here, Lisa – who gave in to Herman’s courting in the second scene after highly emotional inner struggles, who withdrew from her fiancé and invited Herman to an assignation in the third scene, and sent him away, apparently for good, when faced with the corpse of the old Countess in the fourth scene – acts in favour of her love one last time. Her hope, however, of convincing Herman to flee and begin a new life together, far away from fateful St. Petersburg, is dashed, as Herman can now only focus on the money. Lisa, berating herself for having enabled him to take this fatal path, accepts this as her own guilt: by taking her own life, she atones for her own aberration as much as his.

Tchaikovsky had experience with great, painful and unrequited love. Yet he did not choose death. THE QUEEN OF SPADES was followed by his last opera, YOLANTA, a utopia of ennobling, character-altering love that even has the power to heal bodily incapacity (Yolanta’s blindness). In THE QUEEN OF SPADES, however, love makes its sufferers blind and ill, ultimately leading to madness, loss of self and death, with the relentless, overwhelming forcefulness of the dramas of antiquity.

Translation: Alexa Nieschlag