Vasily Barkhatov – Mein Seelenort: Russische Literatur - Deutsche Oper Berlin

From Libretto #4 (2023)

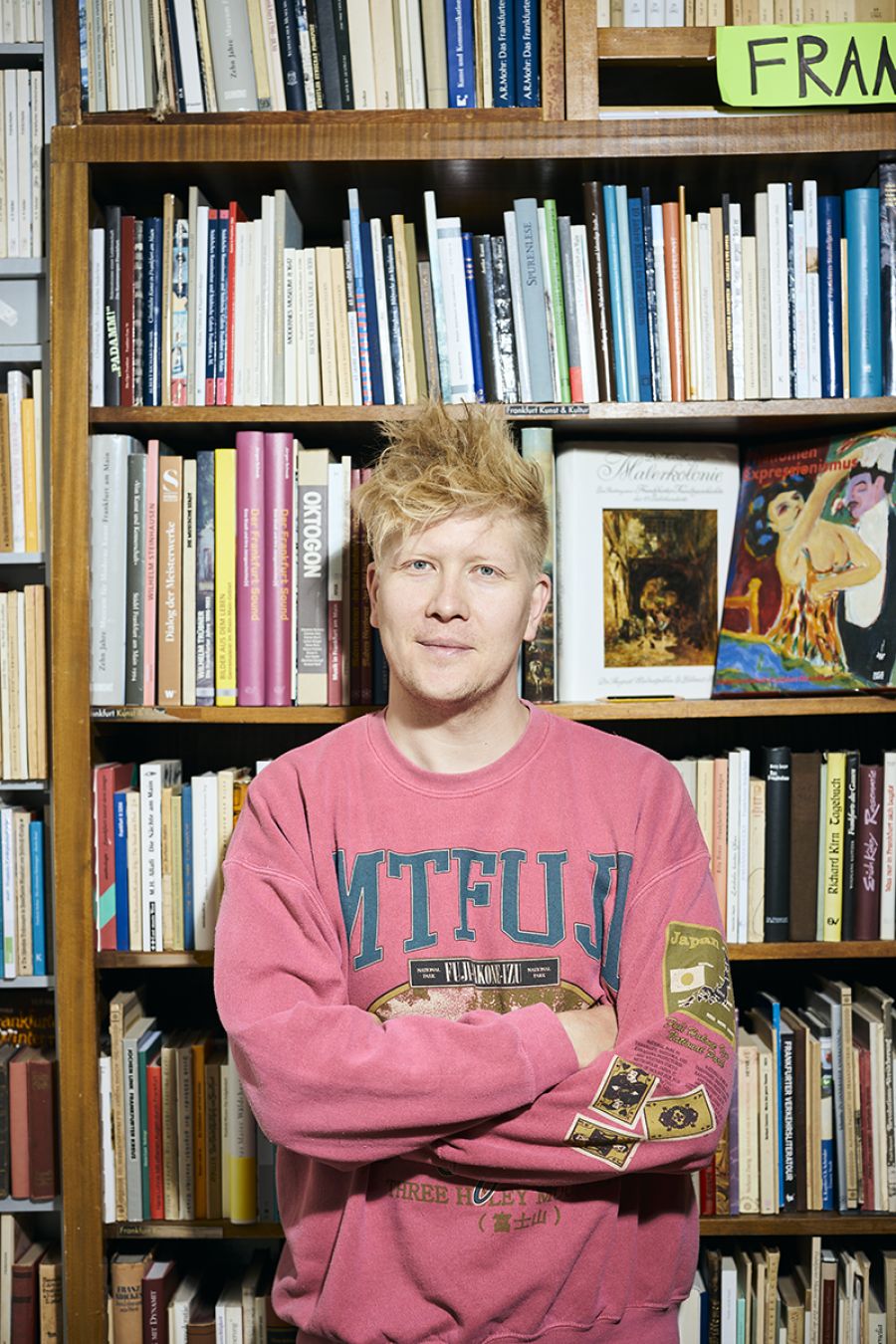

Vasily Barkhatov – My place of serenity: Russian literature

Vasily Barkhatov’s home from home is Russian literature. As a child it was his window on the world; today it’s his font of inspiration. This new star in the directorial firmament is now staging Verdi’s SIMON BOCCANEGRA

I don’t have a private place of peace as such. And no homeland either. I’ve never been deeply bound to an area of land. It could be that I’m scared of conferring that kind of status on a particular location because it might turn out to be an Achilles heel for me.

Although I haven’t lived in Russia for a decade, I still carry the motherland with me because my Russia has always been Russian literature. Ever since I was a child, I’ve loved books. I’m addicted to paper. My father is a journalist and author and we had shelves and shelves of books in our flat in Moscow. I would play with my toys surrounded by walls of encyclopaedias and the collected works of Pushkin, Chekhov, Gogol and Schiller, all with their different coloured bindings and names and titles in Cyrillic script. To me, our library was a kind of treasure trove and Orthodox altar rolled into one. The thought of all those letters and words and sentences and thoughts was utterly mindboggling! Thinking back to those days, I realise the library was like an Egyptian pyramid the way it filled me with awe. How was such a thing possible, I wondered? And when did they write it all down? I already knew I’d never get to read all those books, even if I went at it all my waking hours.

I think of books as companions that allow you to discover the nature of individuals and the world around us. I cribbed this idea from Alexander Sokurov, one of Russia’s best-known film directors and political activists. He once told me that he’d taken all his inspiration from books. That runs counter to the teachings of my Academy professors, who insisted that experience is the mother of all inspiration. But I don’t have to live and feel everything at first hand when books contain the collected experience of humanity. I haven’t got a favourite author, let alone a favourite book. The book I’ve got in my hands is decided by what I’m doing when. Not that there aren’t books that surface again and again: the book I’ve read most often is probably »Moscow to the End of the Line« by Venedikt Yerofeyev, a great example of absurdist post-modern Russian literature. It’s a story told in the first person of a guy travelling by rail to the small town of Petushki, getting increasingly drunk from station to station. A gritty read, but beautiful and magical.

It's not that easy to find Russian-language libraries outside of Russia. Sometimes you get Russian books in antiquarian bookshops. Right now I’m in Frankfurt for a production, and there the Embassy actually owns the Russian library – and I’m giving the place a wide berth at the moment. I’m anti any type of war, especially Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine. It’s hard for me to talk about it. Any words I can come up with all sound pathetic when you consider the awful stuff that people are going through, in both countries. My head kind of implodes whenever I try to reflect on the situation objectively. It’s like a system error in a computer: I can’t get my brain around the scale of destruction. Thinking about it all chills me with terror. As Friedrich Nietzsche put it: if you peer into the void long enough, the void peers into you.

My production of Giuseppe Verdi’s SIMON BOCCANEGRA is about the void within. It’s a very political opera about how power structures eat away at people. I want to point up the way family and happiness on the one hand and a political career on the other are mutually exclusive states. You have to plump for one or the other, not both. One of the two will always suffer – and 99% of the time it’s the family. You’re going to lose it – either physically or spiritually.

We kick off with Verdi’s overture from the first version of the opera. We show Fiesco, a patrician, moving into the White House of its day, the Doge’s Palace, with his wife and daughter – and we are witness to him losing them. Then the focus switches to Simon Boccanegra, the Doge, who’s already alienated everyone around him and never got around to settling down and starting a family. The opera concludes with Gabriele Adorno, a nobleman, and his wife, Amelia, joyfully taking up residence in the Doge’s Palace – and we can predict how the story will end.

Sometimes I wonder why we’re still doing works for the stage. Compared to the catastrophe unfolding in Ukraine, it’s all so childish. My life hasn’t changed at all since war broke out: I go to the rehearsal room and give people instructions. Every day I get to thinking: What am I actually doing here? And why? Maybe I just want to restore equilibrium, to remind people that Russia is not only a country of tanks and missiles; it’s also a world of amazing literature, music and theatre. I don’t want to be ashamed of being Russian.

Recorded by Jana Petersen