Meister der Oberfläche - Deutsche Oper Berlin

From Libretto #6 (2024/25)

Master of the superficial

A hugely gifted innovator or a canny businessman? Richard Strauss had few peers in terms of productivity or versatility. Head dramaturg Jörg Königsdorf on the first Modernist composer

We can assume Jacques Durand thought it would turn out differently. The French publisher had actually managed to organise a dinner encounter, after a Strauss concert, between the great German avant-gardist and his French counterpart Claude Debussy. But instead of a refined conversation which might have yielded fascinating insights into artistic motivations and approaches, the gastronomic summit fell flat. Strauss, who always had one eye on revenues and royalties, held forth on the subject of the music business while Debussy looked on, aghast. After the meal on 26th March 1906 they would never meet again. According to his biographer Matthew Boyden, Strauss opined that Debussy had nothing to say for himself; Debussy on the other hand found Strauss repellent.

Richard Strauss is also remarkable for the number of anecdotes related about him – with a large portion of them conveying degrees of astonishment that such an obviously blessed musician could equally well turn out to be a somewhat ignorant human being. The long list of stories ranges from harmless trivialities such as him cheating at cards to the more serious charge that Strauss cosied up to the National Socialists and tuned out the cultural barbarism of the »Third Reich«.

One reason why this cannot be played down is that parallels are often drawn between Strauss’s middle-class existence and his music. The name Richard Strauss conjures up in many the image of a detached, gimmicky composer of showy works that lack an intellectual element – a man Adorno called a »composition machine« who produced shiny pieces devoid of inner value, or a prime embodiment of that famous axiom: a first-class writer of second-class music.

In downgrading his achievements, people forget that Strauss, who was born in 1864, should not be seen as a 19th-century composer but rather as the first writer of 20th-century music; not the last of the Late Romantics bursting with moral fibre but an artist who was coining a neutral, impartial musical language to interpret the complexity of the modern world, a world in which conscious and subconscious knowledge, the banal, the comic and the heroic existed on a par with one another and in a concentrated ball of multifaceted perception. Wagner’s rarefied pathos will not be found in Strauss’s work. Inconceivable that an opera by Strauss would close with the emergence of a new saviour of society, akin to Wagner’s Parsifal. A psychologically complex character from Strauss, such as Elektra or the Dyer’s Wife in THE WOMAN WITHOUT A SHADOW, is much closer to Berg’s Wozzeck than to Wagner’s Brünnhilde. Suffice to say that Strauss moulded his opera characters within the parameters of traditional tonality, and those tools were all he needed to tell his stories.

It's more useful to regard Richard Strauss as an artist who, even when well advanced in years, was fully abreast of the zeitgeist - and often ahead of the curve. Just as SALOME and ELEKTRA in the early 1900s were the first operas to reflect the ideas of Sigmund Freud, his INTERMEZZO (1924) can be read as one of the first examples of zeitoper, or ultra-topical opera whose storylines deal with the here and now – INTERMEZZO also having a dollop of self-irony mixed in, which tells us that Strauss was well aware that his own lifestyle had little in common with the romantic image of the artist. Even the Apollonian Classicism of later operas such as his DAPHNE and CAPRICCIO can be seen as a comment on the current affairs of his day, as smart productions have long been demonstrating. We see a composer who has portrayed every aspect of life in his works turning his back on the world and fashioning a better version for himself. Because even his art falters in the face of terror and dictatorship.

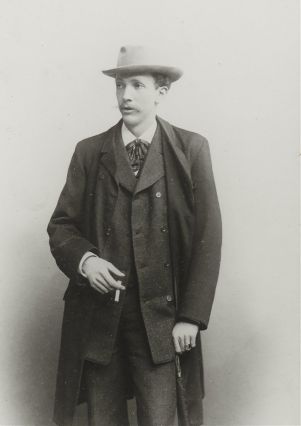

![Siebzigjährig ist Strauss auf dem Höhepunkt seines Erfolgs, gerade hat er ARABELLA in Dresden uraufgeführt [Foto von 1934] © Allstar Picture Library Ltd – Alamy Stock Photo Siebzigjährig ist Strauss auf dem Höhepunkt seines Erfolgs, gerade hat er ARABELLA in Dresden uraufgeführt [Foto von 1934] © Allstar Picture Library Ltd – Alamy Stock Photo](https://imgtoolkit.culturebase.org?color=F7F7F7&quality=8&ar_method=cropIn&file=https%3A%2F%2Fimg.culturebase.org%2F8%2F8%2F6%2Ff%2F9%2Fpic_1737640870_886f9b95762ae002f2567aa7c4422160.jpeg&do=cropOut&width=1240&height=600)