Strauss, komm raus - Deutsche Oper Berlin

What moves me

Strauss, show yourself

Our Richard Strauss cycle comes to a grand close with THE WOMAN WITHOUT A SHADOW, a tale about couples and relationships. Director Tobias Kratzer shares his thoughts on the composer.

It was meant to be the opera to end all operas, a masterpiece waiting to happen. But as is so often the case, masterpieces can’t be painted by numbers. Aiming to create their own fairy tale set to music, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Richard Strauss pulled out all the stops with their Freudian constellations and archaic characters. Their WOMAN WITHOUT A SHADOW ended up being so loaded with material and ideas that pundits still debate what the work is actually about. When it came to marketing the opera, Strauss was tight-lipped on the subject, so directors are advised to choose an understated approach.

THE WOMAN WITHOUT A SHADOW rounds off the Strauss cycle. It’s the earliest of the selected works and the most complex, so it’s logical that we’re doing it at the end, when the themes and expository styles of the other two have already been presented. All three works explore a particular stage of a relationship and are a test of Richard Strauss’s relevance to present-day themes.

ARABELLA shows the emancipation process of the title character and lent itself to being staged as a transgender journey taken by the Zdenka/Zdenko. INTERMEZZO sets out the twists and turns of a composer’s marriage. It’s done playfully, with emphatic beats, using Strauss’s typically flowing orchestral sound, as a kind of early version of today’s autofiction.

THE WOMAN WITHOUT A SHADOW is the synthesis of the themes hitherto presented: man, woman, family, class, society, roles and conflicts. At its core is a tale of the difficulties to be surmounted on the way to bearing longed-for children. An emperor and his wife are suffering from the Empress’s lack of a shadow, a metaphor for her inability to have children. They turn to another married couple in an attempt to buy a reversal of fortune. The story sounds simple, but runs into a cul-de-sac of moral complexity. Why does the happiness of some couples depend on their ability to have children? How classist is surrogate motherhood? To what extent is women’s self-confidence still reliant on their fecundity? All questions that go straight to the heart of the current debate – and to which there are no easy answers.

When at long last everything ends euphorically for all protagonists – joy through pregnancy being this opera’s sole narrative – we’re all left decidedly drained. Self-doubt, suspicion, a chorus of the unborn, Keikobad (the unseen, never singing, yet omnipresent master of the spirit realm)… We’ve been subject to such a parade of patriarchal attitudes, conjugal despair and misogyny that accepting, far less celebrating, the final scene is not a viable response for us moderns.

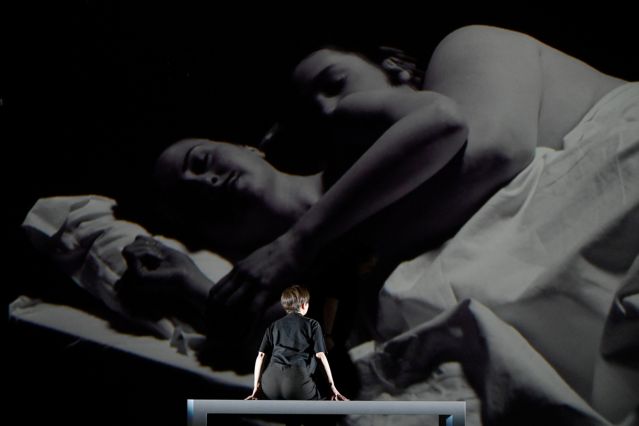

The opera’s themes are on plain view without having to be exaggerated. Instead of cluttering the production with symbolic furniture, we’ve adopted the feel of INTERMEZZO and treated it as an anecdote involving two parallel marriages. THE WOMAN WITHOUT A SHADOW is packed with folksy locations and scene shifts – and we’re staying faithful to all that in our variable sets. We hop from one world to another in quasi-allusive fashion. There’s a relaxed Brechtian theatricality to it and we’re hoping to lay bare the opera’s inner truth and capture the tragic condition of the characters.

THE WOMAN WITHOUT A SHADOW marks the end of a very pleasant collaboration with Donald Runnicles. It began with our joint work on THE DWARF, which was what spawned the idea of mounting this cycle. The works gel perfectly with the DNA of the Deutsche Oper Berlin and the directorial DNA of Runnicles himself, who’s an expert at harnessing the combined resources of the house. I’ve felt very secure here and with him, working at a high pitch of cultivated interaction, which is not only about laying out the form, pathos, emotionality and musical emphasis in representative style but also about seeking a deeper truth – and settling on a form that can stand up to intellectual analysis. That was our objective in crafting the cycle. If we achieve only half of the hoped-for tension in an opera that for most directors is used as a gauge of their failure, then I can begin my incumbency at the Staatsoper Hamburg with a good feeling. Just kidding. Seriously, though, this is my last production as an independent director. That’s reason enough to like this opera.